Batavia’s story has been revealed in pictures for more than 370 years – from the engravings illustrating Pelsaert’s account, published in 1647, to modern three-dimensional photogrammetry of the wreck. The pictures help us show what happened and study what remains.

To make an engraving, you cut the lines of the picture into a metal plate using a sharp tool called a burin. Then you cover the plate in ink and press it against some paper, to transfer the inked lines. There’s a lot of detail in the engravings about Batavia but, as they were made years after the events, there are some mistakes. For example, spot the differences in the two pictures of Batavia below: one image shows it with two rows of gun ports, but it only had one.

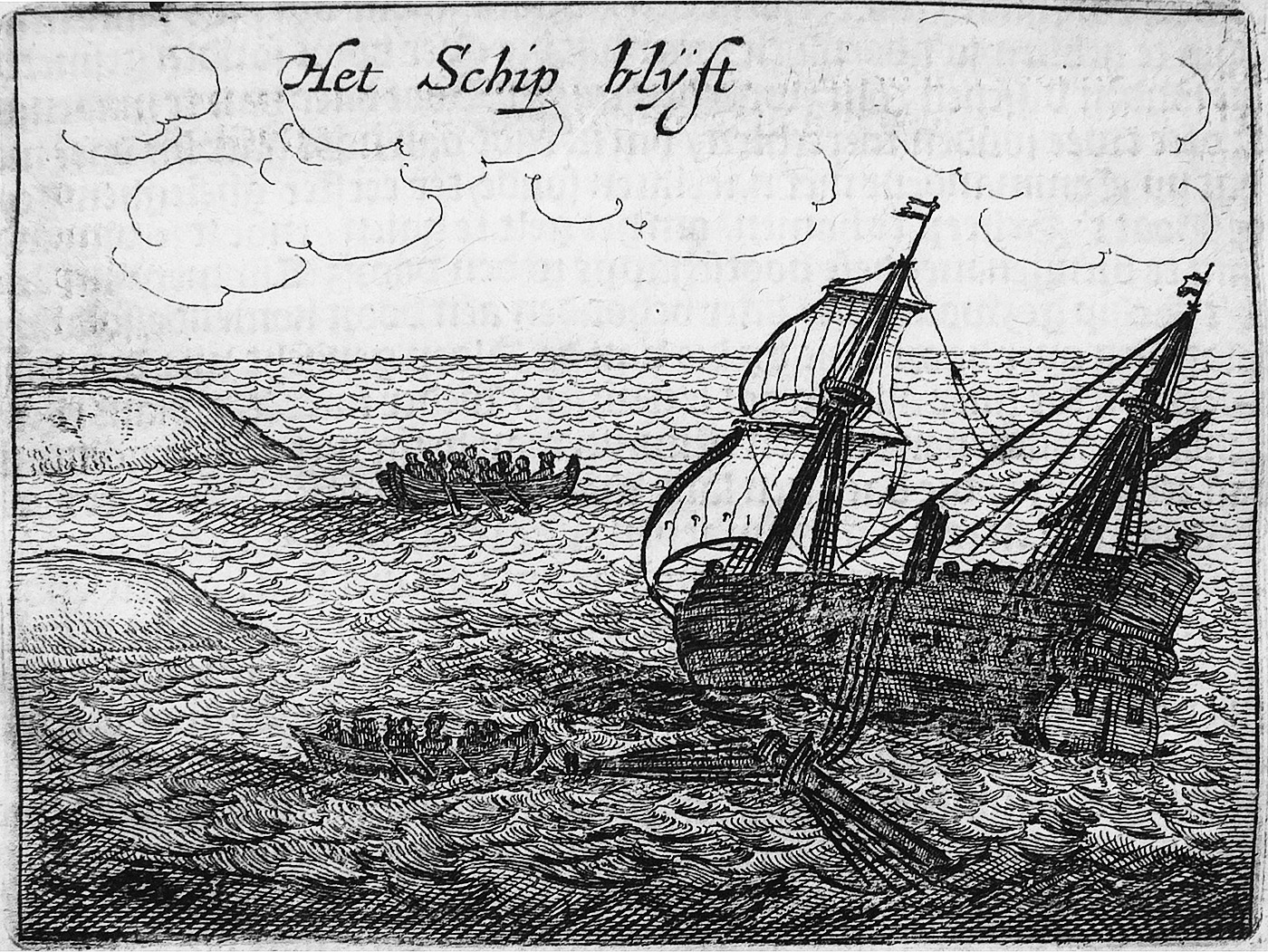

Batavia shown with one row of gun ports. Engraving from Hartgers 1651 edition. The two boats are taking survivors to the nearby Islands.

Batavia shown with one row of gun ports. Engraving from Hartgers 1651 edition. The two boats are taking survivors to the nearby Islands.

The WA Museum started documenting Batavia in 1970. They used film cameras and sketches to record the wreck and artefacts. Film cameras could only take 36 shots, then you had to surface to change the roll. The archaeologists built a darkroom on Beacon Island and developed all the film at the end of every day, so they could check the images.

Batavia shown with two rows of gun ports. Engraving from Pelsaert’s journal published, 1647. ANMM collection.

Batavia shown with two rows of gun ports. Engraving from Pelsaert’s journal published, 1647. ANMM collection.

Stereoscopes allowed 2D photographs to look 3D. Multiple photographs were painstakingly joined together to form photomosaics of the site.

Today digital cameras and specialised software make things much easier ̶ you can take thousands of shots and check them instantly. We can digitise old photographs, create detailed 3D models, film with underwater robots and use drones to look at sites from the air. The WA Museum has even developed a Virtual Reality simulation of Beacon Island that includes grave sites of Batavia’s castaways.

You can explore it here: bit.ly/3bBBHE7