Archaeologists recovered 166 sandstone blocks weighing about 27 tonnes from the Batavia wreck. The blocks had been used to ballast the ship, to help its stability, but their carefully carved shapes showed they were clearly more than that. It was like a giant LEGO® set, with no instructions. They had to work out what it made.

The key came, literally, when they found the keystone, a distinctively shaped piece from the top of the arch. It matched drawings of the water port, the gateway to the Castle Batavia, the home of the VOC Governor General for the East Indies. The VOC couldn’t source the stone in Indonesia or the Netherlands, so they had it carved in Germany and shipped it out to Batavia.

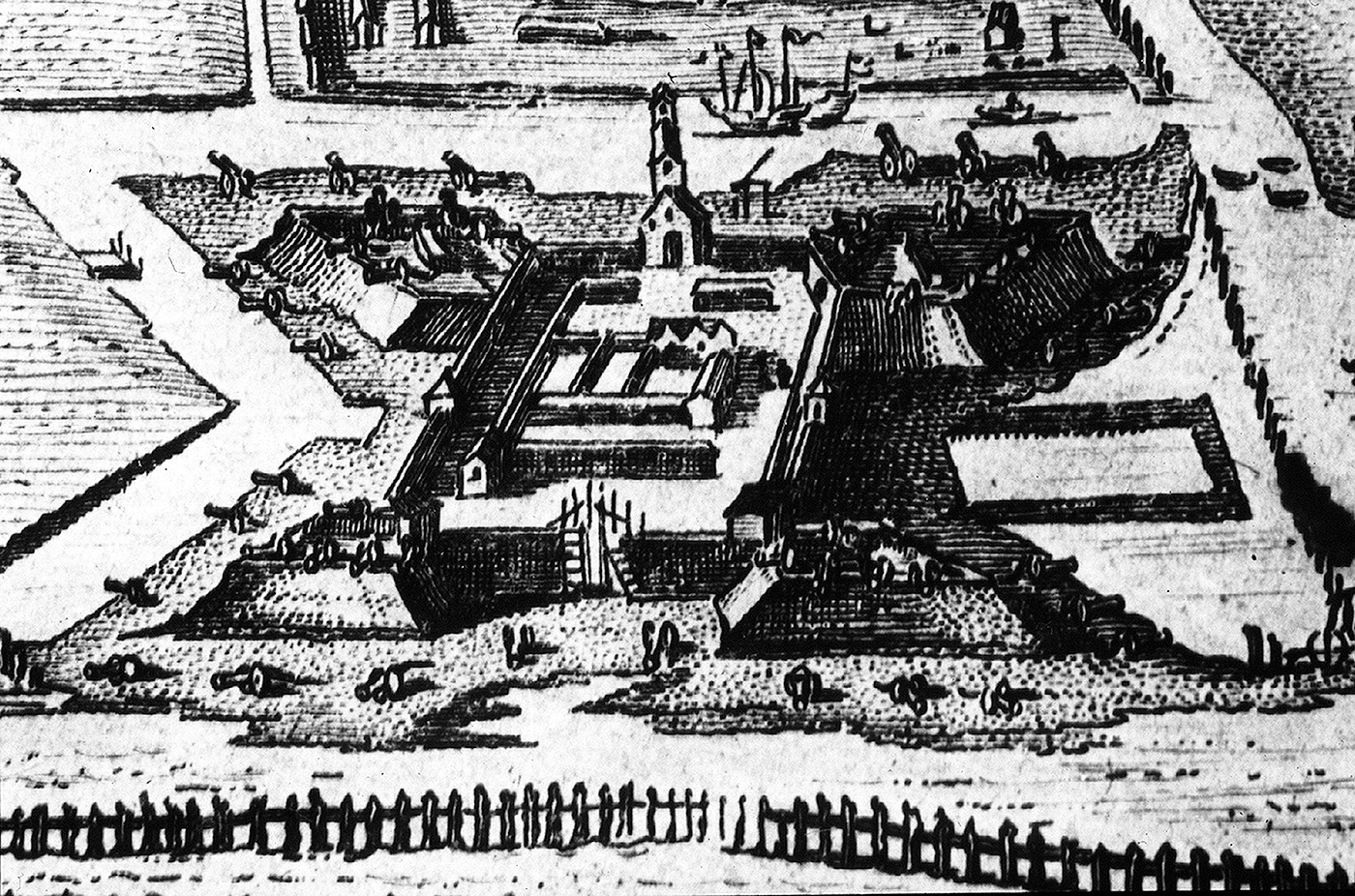

Van der Broek’s illustration showing the waterport. From the book Pieter van den Broecke in Azië

Van der Broek’s illustration showing the waterport. From the book Pieter van den Broecke in Azië

Now the archaeologists knew what to aim for, but they still had to put it together. Some of the pieces were numbered, which suggested how they might stack up. But many weren’t, and the blocks are really heavy, so it was hard to swap them around and try different formats. The archaeologists made a scale model, which was much easier to play with and helped them work it out. They discovered they had the complete portico, plus some extra window surrounds.

Castle Batavia was demolished in 1809, but you can see its lost portico at the Museum of Geraldton in Western Australia.

Geoff Kimpton assembling the portico. Photo from WA Museum

Geoff Kimpton assembling the portico. Photo from WA Museum

3D MODEL

This model of the portico was 3D printed in sandstone. The printer starts with a bed of fine sandstone powder, then applies a binding agent onto the powder, in the shape of the item. It does this again and again, to build it up layer by layer. The powder can also be coloured.

Making the Styrofoam model. Photo from WA Museum

Making the Styrofoam model. Photo from WA Museum

Before the invention of 3D printing, researchers made models by hand. Museum archaeologists made Styrofoam versions of the portico blocks to work out how they went together.